As the learning of Aikido’s principles evolves through its fundamental steps, practitioners face increasing difficulties in handling the techniques, getting the point and understanding how they work and what is their purpose.

Yonkyo, the fourth principle is somehow a mistery box, a technique that can be described and replicated -as every other technique, indeed- yet if you visit a Dojo during a yonkyo class, you will probably see some people feeling a bit of frustration and some other experiencing a lot of pain. In the middle, a lot of people with an enormous question mark on their faces while attempting to find the exact point onto which they should apply a certain pressure in order to control the radial nerve on the partner’s forearm, so that they may control him thanks to a sudden pain.

Many dialogues, even if not spoken, in that occasion may sound as follows:

“Did I get it?”

“Does it hurt?/Is it painful?”

“When will all this end?” and so on.

As for every other Aikido technique, we ought not to forget that it roots on the ground of centuries of studies about how to subdue an enemy, ending as fast as it is possible a conflict. Which meant surviving imposing others huge loads of pain or death.

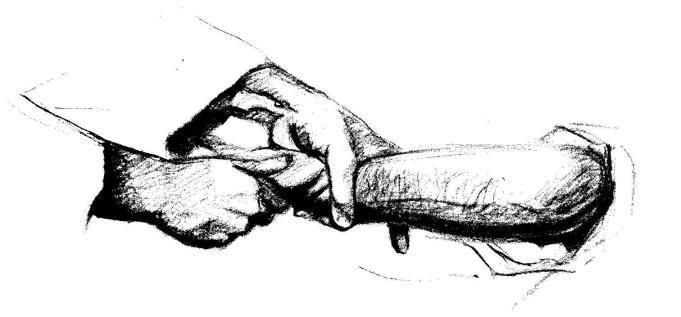

Therefore, basically yonkyo is a tecnhnique that it is based onto the study of using and dosing the knowledge of how the radial nerve passes through the arm down to the wrists and hands in order to control the partner’s center, balance and movement.

Yet maybe there are several other perspectives from which we can refer to yonkyo, as the study of Budo should foresee.

If we look at the point on the forearm onto which yonkyo should be applied, we can see that it corresponds to the points that have been investigated by Eastern traditions for healing cardiopulmonary diseases. In Shiatsu and Acupuncture they are known as Tai en (on the lung meridian) and Nai kan, (on the master of heart meridian).

So, probably, if we are studying a technique in a way we can replicate it thousands of times because our commitment is to preserve both us and our partner, surely we won’t destroy our partner’s arm or his nerves.

So, why are we putting an effort into understanding yonkyo? Maybe the answer could be simultaneously subtle and evident.

If Aikido is the “art of peace” and a novel way to unify and to connect, yonkyo could be a doorway to connect us to our partners’ heart and inner system, and, at the same time, we could take care of them, offering them a kind of treatment, helping them to feel better.

Yet, the tangible aspects of the Aikido practice strongly suggest us to be aware that if we want to walk on subtle paths of Budo, we must understand the basics of jutsu. This pendular movement, over time, gives to the martial artist the gift of a dynamic balance, avoiding therefore to forget the jutsu preferring Budo or viceversa.

Quoting a story reported by Bruce Lee, a Zen master, who practiced the way of the Japanese kempo, during a period of serious illness that would eventually lead him to death, faced with the requests of some of his students about what was the “secret” of his art. He replied saying that there was no secret. At the beginning of his apprenticeship (says the teacher in history) for him a kick and a fist were just a kick and a fist. When he became an expert in the art, he understood that a kick and a fist were something more because they were “full” of a meaning that only those who practiced the art would have understood.

As a result of his old age and because of the increased wisdom that ensued and perhaps also due to the debilitating illness, the teacher told his students that he realized that at the end, a kick and a fist are nothing more than a kick and a fist.

And yonkyo will continue to fascinate thousands of students.